Книга: Code 2.0

A Dot’s Life

A Dot’s Life

There are many ways to think about “regulation.” I want to think about it from the perspective of someone who is regulated, or, what is different, constrained. That someone regulated is represented by this (pathetic) dot — a creature (you or me) subject to different regulations that might have the effect of constraining (or as we’ll see, enabling) the dot’s behavior. By describing the various constraints that might bear on this individual, I hope to show you something about how these constraints function together.

Here then is the dot.

How is this dot “regulated”?

Let’s start with something easy: smoking. If you want to smoke, what constraints do you face? What factors regulate your decision to smoke or not?

One constraint is legal. In some places at least, laws regulate smoking — if you are under eighteen, the law says that cigarettes cannot be sold to you. If you are under twenty-six, cigarettes cannot be sold to you unless the seller checks your ID. Laws also regulate where smoking is permitted — not in O’Hare Airport, on an airplane, or in an elevator, for instance. In these two ways at least, laws aim to direct smoking behavior. They operate as a kind of constraint on an individual who wants to smoke.

But laws are not the most significant constraints on smoking. Smokers in the United States certainly feel their freedom regulated, even if only rarely by the law. There are no smoking police, and smoking courts are still quite rare. Rather, smokers in America are regulated by norms. Norms say that one doesn’t light a cigarette in a private car without first asking permission of the other passengers. They also say, however, that one needn’t ask permission to smoke at a picnic. Norms say that others can ask you to stop smoking at a restaurant, or that you never smoke during a meal. These norms effect a certain constraint, and this constraint regulates smoking behavior.

Laws and norms are still not the only forces regulating smoking behavior. The market is also a constraint. The price of cigarettes is a constraint on your ability to smoke — change the price, and you change this constraint. Likewise with quality. If the market supplies a variety of cigarettes of widely varying quality and price, your ability to select the kind of cigarette you want increases; increasing choice here reduces constraint.

Finally, there are the constraints created by the technology of cigarettes, or by the technologies affecting their supply.[7] Nicotine-treated cigarettes are addictive and therefore create a greater constraint on smoking than untreated cigarettes. Smokeless cigarettes present less of a constraint because they can be smoked in more places. Cigarettes with a strong odor present more of a constraint because they can be smoked in fewer places. How the cigarette is, how it is designed, how it is built — in a word, its architecture — affects the constraints faced by a smoker.

Thus, four constraints regulate this pathetic dot — the law, social norms, the market, and architecture — and the “regulation” of this dot is the sum of these four constraints. Changes in any one will affect the regulation of the whole. Some constraints will support others; some may undermine others. Thus, “changes in technology may usher in changes in . . . norms”,[8] and the other way around. A complete view, therefore, must consider these four modalities together.

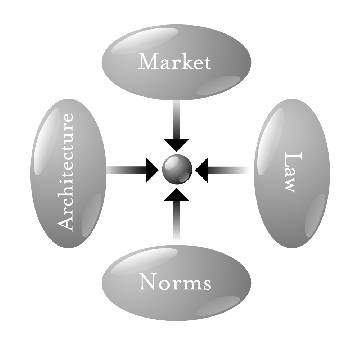

So think of the four together like this:

In this drawing, each oval represents one kind of constraint operating on our pathetic dot in the center. Each constraint imposes a different kind of cost on the dot for engaging in the relevant behavior — in this case, smoking. The cost from norms is different from the market cost, which is different from the cost from law and the cost from the (cancerous) architecture of cigarettes.

The constraints are distinct, yet they are plainly interdependent. Each can support or oppose the others. Technologies can undermine norms and laws; they can also support them. Some constraints make others possible; others make some impossible. Constraints work together, though they function differently and the effect of each is distinct. Norms constrain through the stigma that a community imposes; markets constrain through the price that they exact; architectures constrain through the physical burdens they impose; and law constrains through the punishment it threatens.

We can call each constraint a “regulator”, and we can think of each as a distinct modality of regulation. Each modality has a complex nature, and the interaction among these four is also hard to describe. I’ve worked through this complexity more completely in the appendix. But for now, it is enough to see that they are linked and that, in a sense, they combine to produce the regulation to which our pathetic dot is subject in any given area.

We can use the same model to describe the regulation of behavior in cyberspace.[9]

Law regulates behavior in cyberspace. Copyright law, defamation law, and obscenity laws all continue to threaten ex post sanction for the violation of legal rights. How well law regulates, or how efficiently, is a different question: In some cases it does so more efficiently, in some cases less. But whether better or not, law continues to threaten a certain consequence if it is defied. Legislatures enact[10]; prosecutors threaten[11]; courts convict[12].

Norms also regulate behavior in cyberspace. Talk about Democratic politics in the alt.knitting newsgroup, and you open yourself to flaming; “spoof” someone’s identity in a MUD, and you may find yourself “toaded”[13]; talk too much in a discussion list, and you are likely to be placed on a common bozo filter. In each case, a set of understandings constrain behavior, again through the threat of ex post sanctions imposed by a community[14].

Markets regulate behavior in cyberspace. Pricing structures constrain access, and if they do not, busy signals do. (AOL learned this quite dramatically when it shifted from an hourly to a flat-rate pricing plan.[15]) Areas of the Web are beginning to charge for access, as online services have for some time. Advertisers reward popular sites; online services drop low-population forums. These behaviors are all a function of market constraints and market opportunity. They are all, in this sense, regulations of the market.

Finally, an analog for architecture regulates behavior in cyberspace — code. The software and hardware that make cyberspace what it is constitute a set of constraints on how you can behave. The substance of these constraints may vary, but they are experienced as conditions on your access to cyberspace. In some places (online services such as AOL, for instance) you must enter a password before you gain access; in other places you can enter whether identified or not[16]. In some places the transactions you engage in produce traces that link the transactions (the “mouse droppings”) back to you; in other places this link is achieved only if you want it to be[17]. In some places you can choose to speak a language that only the recipient can hear (through encryption)[18]; in other places encryption is not an option[19]. The code or software or architecture or protocols set these features, which are selected by code writers. They constrain some behavior by making other behavior possible or impossible. The code embeds certain values or makes certain values impossible. In this sense, it too is regulation, just as the architectures of real-space codes are regulations.

As in real space, then, these four modalities regulate cyberspace. The same balance exists. As William Mitchell puts it (though he omits the constraint of the market):

Architecture, laws, and customs maintain and represent whatever balance has been struck in real space. As we construct and inhabit cyberspace communities, we will have to make and maintain similar bargains — though they will be embodied in software structures and electronic access controls rather than in architectural arrangements[20].

Laws, norms, the market, and architectures interact to build the environment that “Netizens” know. The code writer, as Ethan Katsh puts it, is the “architect”[21].

But how can we “make and maintain” this balance between modalities? What tools do we have to achieve a different construction? How might the mix of real-space values be carried over to the world of cyberspace? How might the mix be changed if change is desired?

- Liferea

- 1.1 Real Life Examples of Embedded Systems

- 3.4. Life placement – ненавязчивое раскручивание торговой марки

- Особенности отечественного life placement

- Сетевые ресурсы life placement

- 2.2 The life of a thread

- Lifetime Customer Value

- Life: мост между поколениями

- CHAPTER 16 Handling Activity Lifecycle Events

- Life, Death, and Your Activity

- 1.6. Life management и жизненные цели

- Кейс 2.1. California Credit Life Insurance Group